R-Squared and Non-Linear Models

My previous post was about the coefficient of determination and pitfalls that come with using it to compare models. However, the models we were comparing in that post were linear regression models. I limited the discussion to linear models for an important reason: R-squared is not suitable for assessing non-linear model quality.

If you find that surprising, don’t worry - you are not alone. Using R-squared (often denoted \(R^2\)) to describe the quality of non-linear model may be the most common data science error that I see. This mistake is so common that entire papers have been dedicated to addressing it. In this post, I am going to explain the reason why the interpretation of the \(R^2\) statistic assumes a linear model and why it does not extend to non-linear models.

The most general definition of \(R^2\) is this:

\[SS_{res} = \sum_{i} (y_i - f_i)^2 = \sum_{i} e_i^2\] \[SS_{tot} = \sum_{i} (y_i - \bar{y})^2\] \[R^2 = 1 - \frac{SS_{res}}{SS_{tot}}\]\(SS_{res}\) is the sum of the squares of the residuals (i.e. errors \(e_i\)) between the model (\(f_i\)) and the observed samples (\(y_i\)). This is also known as the sum of the squared errors. \(SS_{tot}\) is the total variance observed in the samples about the mean (\(\bar{y}\)). Lastly, \(\frac{SS_{res}}{SS_{tot}}\) is the ratio of residual variance to total variance observed in our dependent variable \(y\). Therefore \(R^2\) is the compliment of this ratio.

In plain english this means that \(R^2\) is the ratio of the variance our model describes to the total variance observed in \(y\). However, there is a hidden assumption here. Lets define the variance described by our model as \(SS_{model}\). Then we can restate \(R^2\) like this:

\[\frac{SS_{model}}{SS_{tot}} = 1 - \frac{SS_{res}}{SS_{tot}} = \frac{SS_{tot}}{SS_{tot}} - \frac{SS_{res}}{SS_{tot}} \implies SS_{model} = SS_{tot} - SS_{res} \implies SS_{tot} = SS_{model} + SS_{res}\]Thus the implication of the definition of \(R^2\) assumes that \(SS_{tot}\) is comprised of two quantities: the variance described by the model and the residual variance. The question we must now ask is whether this holds for any class of model.

Let’s take a closer look at the total variance of the response variable \(SS_{tot}\). Recall that the total variance is composed of each observation’s squared distance from the mean of all observations \(\bar{y}\). It is here that we will introduce the predictions of a generic model \(f_i\). It is important to note that we make no assumptions about the model’s functional form.

\[SS_{tot} = \sum_i (y_i - \bar{y})^2 = \sum_i (y_i - f_i + f_i - \bar{y})^2 = \sum_i ((y_i - f_i) + (f_i - \bar{y}))^2\]See what happened there? We introduced the quantity \(f_i\) by both adding and subtracting it inside the quadratic term. In this way we are able to incorporate the model’s predictions into our variance calculation without breaking the equality. Let’s continue by expanding the quadratic expression.

\[\sum_i ((y_i - f_i) + (f_i - \bar{y}))^2 = \sum_i (y_i - f_i)^2 + (f_i - \bar{y})^2 + 2(y_i - f_i)(f_i - \bar{y})\]Finally, we can distribute the summation operator.

\[\sum_i (y_i - f_i)^2 + (f_i - \bar{y})^2 + 2(y_i - f_i)(f_i - \bar{y}) = \sum_i (y_i - f_i)^2 + \sum_i (f_i - \bar{y})^2 + \sum_i 2(y_i - f_i)(f_i - \bar{y})\]We begin to see some quantities that we are already familiar with:

\[SS_{res} = \sum_i (y_i - f_i)^2\] \[SS_{model} = \sum_i (f_i - \bar{y})^2\]But there is something else in this expression that we have not previously seen. The cross term of the quadratic \(\sum_i 2(y_i - f_i)(f_i - \bar{y})\) stands out as it did not appear when we first deconstructed \(SS_{tot}\). Why not? Let’s analyze the pieces that compose the cross term.

Within the summation, we have a constant \(2\) that we can disregard for now. Then we have the \(i^{th}\) error \((y_i - f_i)\). The error term is multiplied with the \(i^{th}\) prediction shifted by the mean \((f_i - \bar{y})\). The cross term arises due to the interaction between residuals and predictions. It represents the covariance between the errors in the predictions and the (mean-centered) predictions themselves.

To recap, the question we are trying to answer is: Why isn’t \(R^2\) suitable for assessing the fit of a non-linear model? We now have all the pieces we need to answer this question.

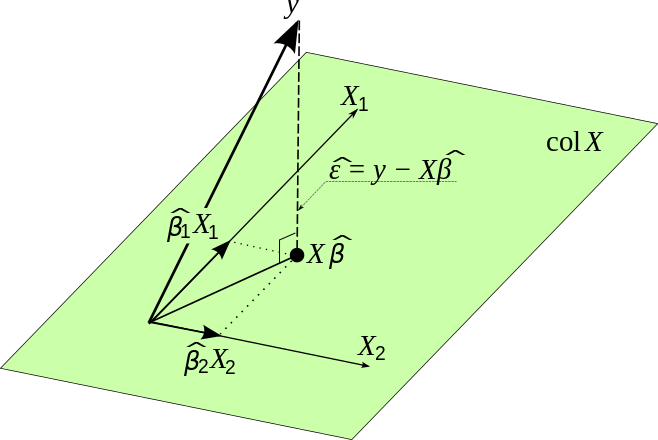

We will start by examining the case when \(f\) is a least-squares linear model. It is important to remember how a model like this is fit to the dataset. I find it especially helpful to consider this optimization problem from the perspective of projecting the dependent variable \(y\) onto the space spanned by the columns of our independent variables \(X\). The linked wikipedia article provides some intuition:

Notice how the error vector denoted by \(\hat{\epsilon}\) in the diagram is perpendicular (i.e. “orthogonal”) to the prediction vector denoted by \(X\hat{\beta}\). The error vector is the rejection of \(y\) projected onto the span of the columns of \(X\). From the geometric perspective, this means that the dot product of the prediction vectors and the error vectors will be zero. From the perspective of probability, this means that the predictions and their errors are independent. Formally, this means the following in the linear least squares setting:

\[\sum_i (y_i - f_i)(f_i - \bar{y}) = 0\]And therefore

\[\sum_i (y_i - f_i)^2 + \sum_i (f_i - \bar{y})^2 + \sum_i 2(y_i - f_i)(f_i - \bar{y}) = SS_{res} + SS_{model} + Other = SS_{res} + SS_{model} = SS_{tot}\]I once heard a mathematician describe linear/non-linear systems in the same manner that Tolstoy describes happy/unhappy families in Anna Karenina:

Linear systems are all alike; every non-linear system is non-linear in its own way.

The point is that while linear models exhibit certain properties, such as the orthogonality between predictions and errors, which simplify the interpretation of \(R^2\), non-linear models do not necessarily adhere to these properties. In particular, the assumption of independence between predictions and errors, which is crucial for the derivation of \(R^2\) as a meaningful measure of model fit, may not hold for non-linear models.

When fitting non-linear models, the relationship between predictions and errors can be more intricate. The errors may depend on the predictions themselves, leading to non-zero covariances between errors and predictions. Consequently, the decomposition of total variance (\(SS_{tot}\)) into variance explained by the model (\(SS_{model}\)) and residual variance (\(SS_{res}\)) becomes more complex.

The presence of non-zero covariances between errors and predictions invalidates the straightforward interpretation of \(R^2\) as the proportion of variance explained by the model. In such cases, \(R^2\) can either overestimate or underestimate the goodness of fit, leading to misleading conclusions about the model’s performance.

To summarize, while \(R^2\) is a valuable metric for assessing model fit in the context of linear regression, its interpretation becomes problematic when applied to non-linear models due to the potential violation of assumptions regarding the independence between predictions and errors. Therefore, caution should be exercised when using \(R^2\) to evaluate non-linear models, and alternative approaches, such as Akaike information criterion (AIC) and/or Bayesian information criterion (BIC), may be more appropriate.